It’s an early Monday evening in June. Liverpool, not always blessed with the best weather this time of year, is experiencing never-ending sunshine. As I walk through the city centre, people flood the streets as they leave work or head towards shops to part with their hard-earned cash.

I’m walking past The Bluecoat, armed with a camera, a Dictaphone, and a notebook filled with questions to ask my previous university lecturer, Jeff Young. I came across his book Wild Twin in Waterstones, which has been shortlisted for the TLS Ackerley Prize 2025, and decided to reach out for an interview.

Wild Twin deals with many things. It addresses identity, memory, and the relationships from Young’s life. However, none of these are possible without his adventures through Europe, which he decides to go on after quitting his 9-5 job.

It’s this aspect of his book that I want to question him on during our interview.

We meet in Caffe Nero in Liverpool One. He drinks a green tea whilst I sip from a hot latte, a bad choice given the weather outside. We spend 15 minutes catching up before diving into the interview.

With my Dictaphone powered on, the first and most appropriate question is a simple one…

What made you want to write Wild Twin now?

I used to teach at John Moore's, creative writing, as you know. Over the years, quite often somebody would say [a story and] I'd say, oh, that reminds me of when I lived in Amsterdam and I did this, this and this.

Quite often, people would say when are you going to write all this down and I’d never thought I would. I'd used bits of my life story in theatre shows and radio dramas and stuff like that, just little extracts, little bits and pieces, but I'd never thought about writing down a whole narrative.

I wrote this memoir GhostTown, which did really well and was nominated for prizes and sold really well.

You do book events and somebody'd say in the Q and A, what's next? My answer was always, I've no idea. I've always done this thing when I started writing for theatre, I got a play on, I didn't even think that there might be a second play, I just thought, oh great, I've had a play on.

When I started working in radio, I had something on the radio, it never occurred to me that you do another and another. It was the same with GhostTown, what's next? I have no idea, I think that's probably it. Then the publisher Little Toller said to me, we want to do another book with you. I said, well I've got all these stories about hitching around Europe and living in squats in Amsterdam, and it was like, let's do it.

It was as simple as that. It was from something that I'd always avoided or didn't even think was [worth] writing down. [It was] like yeah, it's probably time, you know?

I'm in my late 60s, I think this might be the last book but it's like if I'm going do it, now's the time to gather all those stories and memories Paris, Ostend, Amsterdam, and so on and just get them down on paper, and that became Wild Twin.

Part One starts with a quote from Jean Genet, which reads:

‘Worse than not realising the dreams of your youth would be to have been young and never dream at all.’

What tone did you hope this quote would set for the book? Why did you choose it?

I’m a big fan of his work and I'd always had that written down in notebooks. I thought it would keep me focused. It's a tricky thing about when you're writing about memory you can write about memory and be wistful and nostalgic, or you can write about memory and try and be in the absolute moment.

There's an ambiguity to that quote, it suggests to me, be in the moment of those youthful dreams, not an old man looking back into the distant past. Try and focus my memory so sharply that I'm writing it as now, which is why it's in the present tense.

I'm not wistfully nostalgic, remembering, I'm trying bring the moment back to life. I kind of think of memory and dream as being interchangeable. When we remember, we don't remember solid facts, we remember in a dream-like way, and both of those books GhostTown and Wild Twin are attempt to do that.

This book details some of the journeys you took across Europe when you were younger. What were you hoping to learn about yourself that you couldn’t discover in your hometown?

I wanted to be like the beat poets, Jack Kerouac, and all the kind of writers and painters in Paris in the 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, who were living lives where they were creative.

They were also hanging out in cafes, and bars, and nightclubs, and then sort of in competition with each other but also nurturing each other.

I was really interested in scenes, so Greenwich Village in the 50s and 60s, Paris. And in the mid-century, Berlin before the Second World War, Soho in London, those kind of scenes, they are fertile and I was looking for that.

I wanted to see, can I be that? Can I be the poet or the painter, so that I'd never have to be a filing clerk? The whole method of travel was nearly always hitchhiking and I was sort of always interested in the element of risk. I didn't have any money, I set off from Liverpool to go to Paris with 200 quid.

It wasn't like I could buy train tickets or stuff like that or an airplane ticket, I liked it, I liked the kind of borderline poverty and I liked the unplanned nature of hitching. You ended up in the wrong place, I was quite often scared but I guess it was all the opposite of nine to five.

Did you have a particular book that made you want to go over to Europe?

[For] Paris [it] was Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller. I think it's a bit out of fashion Tropic of Cancer. He has a very problematic view of women [that’s] of its time, [the] 1930s, where he very beautifully captures the soul of the city and its flea pit hotels, its dive bars, and the artistic community.

There wasn't a particular book that drew me to Amsterdam. Amsterdam was more about its feeling. I just had a feeling that this is where artists lived and because I lived in squats, the squatting community was full of people from all over Europe.

Even if it was like a graffiti artist or whatever, people had this impulse to make things and the homes they were living in, [they were] making homes out of semi-derelict warehouses.

Out of the places you write about in the book, which one do you remember fondly and wish you could go back in time to revisit?

Well, a few months ago I went to Amsterdam. I went to do a Wild Twin book event in Amsterdam.

It was an event with me and three other writers and they'd all [at] times in their lives, lived in Amsterdam and in some way written about [it]. [There was an] American guy called Chad Bilyeu, an English woman called Ali Miller, and an English guy called Richard James Foster, who still lives in Holland.

So I was on this bill with the four of us, so I went with my family, with my partner and my daughter. The day after the event, we went back to one of the places where I used to live.

It's like a pilgrimage, and this place, it's the second well, it's the third home I had in Amsterdam. It used to be a place where you could just walk in through an alleyway into the communal courtyard, a very beautiful garden.

I went back all these years later, assuming you could still do that. When I got there, it was a gated community. The first reaction, I was shocked, thinking I can't get in. Then we walked away, it was like that's okay, it means it's over, I'd never have to go there again, we'd said goodbye to that house. I was with my daughter and my daughter was like are you okay? I said you know what, yeah it's all right. It's like I've written about it I've attempted a pilgrimage to see it again but I don't have to do that anymore.

We went to Paris while I was writing Wild Twin. Again, the hotel that I stayed in Paris, in the book, I said let's go and look at the hotel, and we got there and it was an IT office. [I] look through the window and there's all these men sitting there on their laptops.

As you know from the book, it's like a dive, with bed bugs and a hole in the floor for the toilet and [now] it's pristine. All [these people] on their Macbooks, and again that was like it's over.

So those are the two places. A lot of the places in the book I wouldn't know how to find them because I found them by accident, by somebody dropping me off in a car on the side of the motorway, and I'm walking for a day through fields, country lanes and I've no idea where they are.

What do you think makes a travelling experience authentic? Do you believe its necessary to go off the tourist path to have one?

Well you see, I do think it's necessary to go off the tourist path. This writer Rebecca Solnitt she wrote a book called, A Field Guide to Getting Lost and the subtitle of Wild Twin is Dream Maps of a Lost Soul and Drifter.

It's kind of my attempt to say a similar thing to that field guide, to getting lost and trying to say that getting lost is okay. We're all very well equipped with our apps on our phones and our guidebooks and our online information.

We're not really looking at the city, we're not really looking at the place we've gone to, we're looking at our phones, and we're looking for security, and that's fine as well, if that's what you need

But you know, the travels in Wild Twin [took place] before mobile phones existed, before the internet existed, and you had to just find out, what was around the corner. There was nobody to say to you, don't go around that corner, don't go down that alley, apart from somebody in a bar might say to you, oh don't go down there.

But my instinct was always to go down the alley if somebody said I wouldn't go down there if I were you.

I'd think I'm going down there and the person, Becks, who I was travelling with would be like come on let’s go down there.

I've never been to Venice but you read about it, you see footage of it. Venice is very overcrowded and people stick to set routes, they go to this white square they go here, there, that church.

[But] what happens if you do go down that alley? You might find another Venice or the real Venice. Rome people go to particular hot spots in Rome.

Liverpool, who walks beyond the city centre? Who thinks, wow, let's go down there? It's kind of a loaded word, authentic isn't it, but the authentic may well be around that corner.

Liverpool's losing its pubs, most cities are losing their pubs but Liverpool pubs are becoming this kind of monoculture.

You know in the old days when pubs were owned or managed by individual landlords and couples or whatever, they had their own identity. But pubs start to look the same and all these new pubs that are opening that pretend to be old pubs, you know established in 1835 but it was actually established last year. They're full of all the old furniture and stuff. Now you can go into those pubs by accident and think well, oh this pub's been here for 200 years but it hasn't it's been here for a week.

So the authentic is not the authentic no longer, [not] even recognisable as a genuine thing.

There’s a litany of characters you mention in the book and has the reader guessing who you’ll meet next.

From the people you write about in Wild Twin, was there someone who taught you an important life lesson? If so, what was that lesson?

Bill the Wolf, I'm older now than Bill the Wolf was when I met him. I thought that he was an old man, but I'm now older than he was then. He had been in a concentration camp during the Second World War.

He was gay, he was very flamboyant. I think I'd describe him in the book as like Amsterdam's Quentin Crisp, magenta hair, silk scarves, make-up.

[He would] walk in the streets [like that] of Amsterdam, which was a very open-minded city, but this is the lesson in the book. He invited us into his home, the part of the squat where he lived.

He learned our situation, that I had hypothermia. I was seriously ill, and he said well come and live with me, we'd been there half an hour and he divided his part of the squat up into two.

He essentially moved into the corridor and he gave us his bedroom and we went to live in his bedroom and the thing that I learned from that, it's about the kindness of strangers. He did kindness and tolerance, an openness, a willingness to help people, you know?

The other guy in the book Robicheau, which was not his real name, he was a really good friend and then he robbed us from our bank account, from my bank account. I sort of learned something from him as well because there came a point where I confronted him about it. I said I'm going to have to go to the police because if I don't go to the police I'm in trouble.

He just kind of like nodded and smiled and shook my hand and said yeah that's what you must do and I thought that was remarkable. It wasn't like do that and I'll kill you, it was like it was acceptance and I did, I went to the police and I shopped him.

The police said yeah he's wanted in like several countries and then I found out all these things about him. He'd been a mercenary, killed people. He's probably dead but that was a learning moment. Me plucking up the courage to say to him I've got to go to police, I've got to shop you and him just going, yeah that's okay and that's something, isn't it?

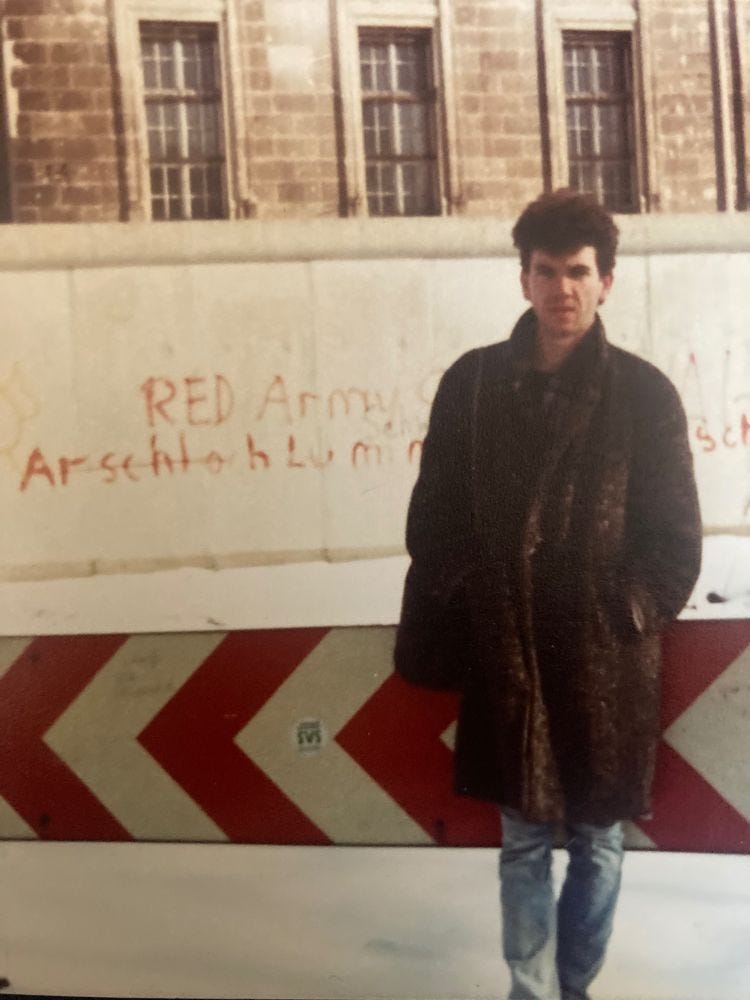

Do you think documenting your travels through photography can undermine the beauty of a memory? Or do you see them as important ways to remember where we’ve been in life?

I'm very attracted to old photographs since the death of my parents and my sister, finding old photographs from childhood caravan holidays and stuff like that are like time capsules, portals into the past.

I think photographs do have a purpose, a value, but I think these days everybody's always taking photographs on their phones. If you're always taking photographs on your phone, you're not actually experiencing the place that you're in; it's being filtered through the screen.

It's like gigs, you go to gigs you realise that you're surrounded by people who aren't listening, watching the band, they're looking through their phones because they're filming or taking photographs of whoever's on the stage. It's like they're not actually living the experience they're living [a] filtered experience, one degree removed.

However, I take photographs all the time not at gigs, I don't do that, but like wandering around. I'm doing it at the moment I'm doing a project for Violetta, the record label [in] Liverpool?

Violetta does a newsletter now, and they've just started. They've come off social media, they're doing an email newsletter to their subscribers and they ask me to do a fortnightly piece. It's a piece [where] I take a photograph and I write about the photograph. It's a photograph about somewhere in the city that means something to me.

The photograph triggers off 200 words, [a] poetic response, and that's a really good form. So I do take photographs but I think there's something more potent about an old photograph that you find in a wardrobe, there's poetry to that, more so than scrolling through your phone and saying this is when I went to the Eiffel Tower.

How has travelling transformed your view of your hometown, Liverpool? What did you see differently in the city when you returned?

There have been times in my life where I haven't wanted to come back. I lived in London in the early 2000s and got priced out, couldn't afford to live there anymore. My partner Amy suggested we move back to Liverpool, I didn't want to come.

I didn't like living in London, but we did for work. I didn't want to come, and then we did, and it was like it was a mixture of things. It was like rediscovering the city, my city, but also finding a new city.

We went to live in a part of the city that I hadn't historically lived in, Aigburth. It was like discovering this part of the city and making new friends, and starting a different kind of work. I started teaching at John Moore's, which I'd never done before.

After Amsterdam, I've never worked this out, but I needed to come back to Liverpool. The conversations with Becks about moving back to Liverpool, she had no interest in moving back to Liverpool whatsoever and I needed to come back to see if I could write, to see if I could be a writer.

When she decided to come, it was on the condition that we stayed for two years because she just wanted to keep travelling. I'd been back just a few months and I was working as a writer, started off doing poetry gigs and very quickly I had a play on in a theatre and then after two years, Becks said, is this what you're doing? and I said yeah I want to do this and she said right I'm going to South America and she did.

I came back to Liverpool then and I didn't particularly know anybody I'd lost touch with my old friends and I started building a new circle of friends and making contact with other artists and writers.

What kind of happened, I was living the life that I'd set out in search of. At the very beginning of those journeys. I was living in an artist's community, we lived in Falkner Square, we were surrounded by artists and poets, [a] mutual self-supporting community.

Liverpool wasn't the Liverpool of working at Merseyside County Council the 9 to 5, it was this Liverpool, kind of the Paris and the Greenwich Village, you know? 80s Toxteth, I like to call it Liverpool 8, was that bohemian place I'd gone in search of.

One last question, it's not going to be what you're planning to do next, but I will end on this question: What do you hope Wild Twin teaches its readers about life?

I hope it teaches people to be less cautious, not to get themselves into dangerous scrapes, but to have the confidence.

It's okay to be a bit less cautious about how you live your day-to-day existence, it's okay to have a bit of a risk factor in there, because having the confidence to take that risk is going to change you in some way.

I think Wild Twin in some ways is a cautionary tale but in other ways it's like a suggestion that it's okay to be a fuck up.

As I get older, my partner Amy says to me I'm really scared of change. I kind of am for justified reasons, I'm getting older, I've got health issues, I'm probably not going to go down the alley at the moment.

But as a younger person, I was all right with that, and it's like I'm probably foolhardy to a degree. But it got me places and I met people, and I did interesting things, and I found interesting places.

So read the book and then think, yeah, I'll go down the alley, I'll go down the alley with a mate.

Wild Twin by Jeff Young is published by Little Toller and available for purchase through Amazon, Waterstones, and other booksellers.